FED shrinking its balance sheet

There have been many references to the FED shrinking its balance sheet recently. This is a good explanation of what it means and why authorities are being so careful not to surprise markets. **JB**

Federal Reserve officials grappling with the legacy of expansive stimulus would find it difficult to return to the central bank’s precrisis role on the sidelines of financial markets, analysts and central-bank watchers say.

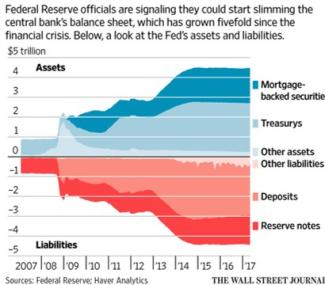

A long list of programs adopted to help foster economic growth, along with changes in money markets and bank regulation, have vastly expanded the Fed’s balance sheet and its involvement in markets. The Fed’s assets now total $4.5 trillion, up from less than $1 trillion a decade ago. Since 2013 the central bank has become one of the largest traders with U.S. taxable money-market funds, according to Crane Data.

Many analysts and investors worry that significantly rolling back the Fed’s expansion, a course advocated by some in conservative circles, risks disrupting markets and the economy at a time when growth remains tepid. It would also reduce the connections the institution has built with a diverse set of Wall Street firms, beyond the group of banks it dealt with before the crisis.

The Fed has become “like an octopus,” said Jeffrey Cleveland, chief economist at Payden & Rygel, a Los Angeles money manager. “Once you get the power and you are influencing all these markets, do you really want to retreat from all that?”

Investors are already assessing how stocks and bonds might react, when the central bank begins the latest stage of its yearslong retreat from stimulus—likely later this year—by ending the practice of reinvesting the proceeds of maturing bonds into new bonds. The Fed is scheduled to publish Wednesday the minutes of its latest policy meeting, where officials may have continued their debate over the mix of policy tools they plan to use in the future.

Some Fed officials say they are attracted to maintaining parts of their current approach. Minutes of their November meeting also showed officials discussing the advantages of keeping something similar to the existing system in place, in part because it is simpler to operate than the precrisis one.

The Fed hasn’t decided the issue, but its choices will be closely watched because its leadership is in transition. President Donald Trump is preparing to fill three vacancies on the Fed’s seven-member board. The White House hasn’t named its picks, but its choices could set Fed policy in new directions, including by limiting its role in markets. Republican lawmakers have also revived legislation to subject its decisions to greater public scrutiny, and some want monetary policy conducted by preset rules.

“It’s not your father’s Fed,” said Adam Gilbert, partner at PricewaterhouseCoopers LLP and a former New York Fed official. Changes could herald “incoming policy makers who are by nature skeptical of a Fed that continues unorthodox approaches to both monetary and regulatory policy.”

New York Fed President William Dudley told an audience this month the portfolio isn’t likely to return to its precrisis size. Federal Reserve Bank of San Francisco President John Williams said this month the portfolio would be “significantly smaller” than it is today, but likely above $2 trillion in assets.

The ultimate size will be closely tied to which system the central bank decides to use to control interest rates in the future. A handful of Fed officials have already begun questioning the wisdom of returning to the blueprint for controlling rates that they used before the crisis, although they have more time to decide.

At the center of the debate is a special investment program the Fed launched in 2013. Through the facility, it lends money-market funds and others Treasurys in exchange for cash, temporarily draining excess cash from money markets and discouraging lenders from lending at rates below the target range for interest rates.

Initially, the central bank said it would reduce the capacity of this so-called reverse repo facility “fairly soon after” it had begun raising short-term rates in 2015. Today, the Fed has no current plans to do so. Mr. Dudley suggested in April the Fed likely wouldn’t phase out the facility.

Without the Fed repos, short-term rates could slip too low, and demand for Treasurys in the open market would surge, causing problems for money-market funds seeking alternative places to park cash overnight. Removing the program would “cause huge dislocations from a bond-market standpoint,” said Debbie Cunningham, chief investment officer for global money markets at Federated Investors.

A balance sheet that is smaller than today’s, yet still substantial, would enable the Fed to keep the reverse repos around. It would also support the Fed’s foreign repos for overseas accounts, where weekly balances have averaged $250 billion, up from $30 billion precrisis, as well as the $1.5 trillion in currency outstanding and changing cash-management policies at the Treasury Department.

If the Fed reduces its bond portfolio, the burden will be on private market participants to step in. In 2018, Morgan Stanley calculates investors may have to absorb $400 billion in mortgage bonds alone, a level not seen since 2008. In the past, such transitions were smoothed by the banks authorized to trade opposite the Fed, called primary dealers. Now those firms are grappling with new leverage rules, and some have less capacity.

Communicating a strategy for unwinding risks some unintended signals. In 2013, when the Fed surprised investors with talk of slowing bond purchases, financial markets convulsed, thinking the Fed meant earlier rate rises than were expected.

The Fed is wary of destabilizing the Treasury market, in particular, because of increasing lurches driven by algorithmic trading. To avoid market disruptions, former Fed Chairman Ben Bernanke wrote in a recent blog post for the Brookings Institution, “There’s no need to rush.”

By Katy Burne WSJ Updated May 21, 2017 12:15 p.m. ET

Write to Katy Burne at katy.burne@wsj.com